Moiré Jewelry

New Window × David Derksen

The Moiré Jewelry are for sale in our shop.It's a couple of weeks before the Dutch Design Week and we find ourselves in David Derksen's studio. He finished his Moiré Jewelry collection and installed it in his cabinet—his offline window so to speak—that will be on display at our presentation in the Klokgebouw. His cabinet will show both the process and final result of his project. In this interview we will dig deeper into David's work and the realisation of Moiré Jewelry.

What was the first thing that triggered you to create Moiré Jewelry?

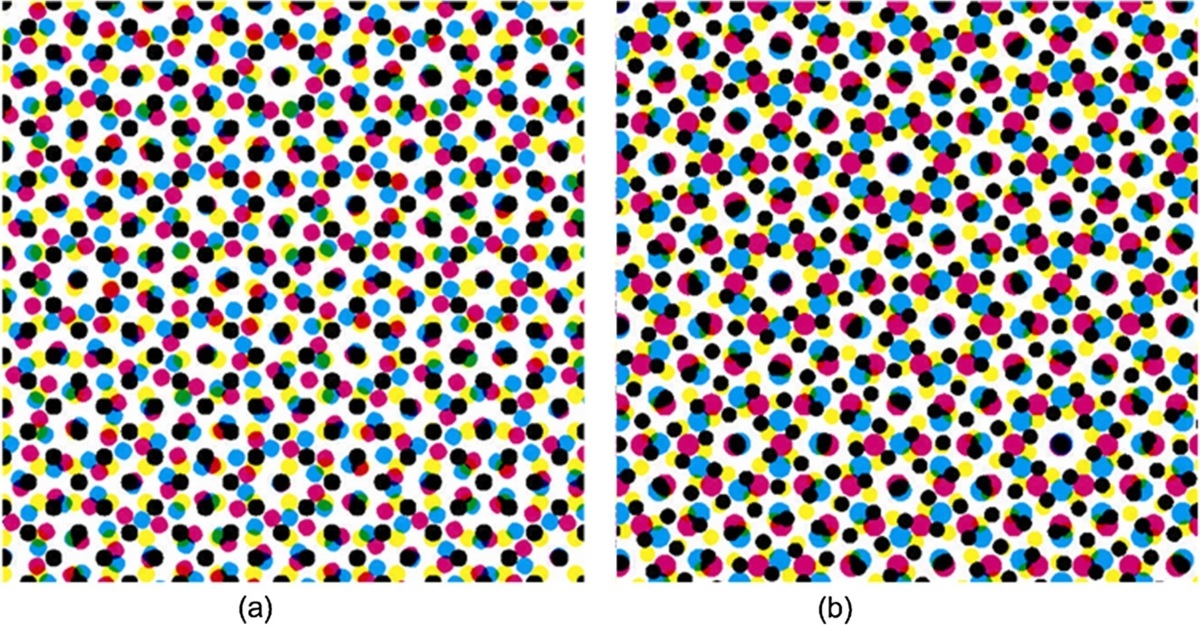

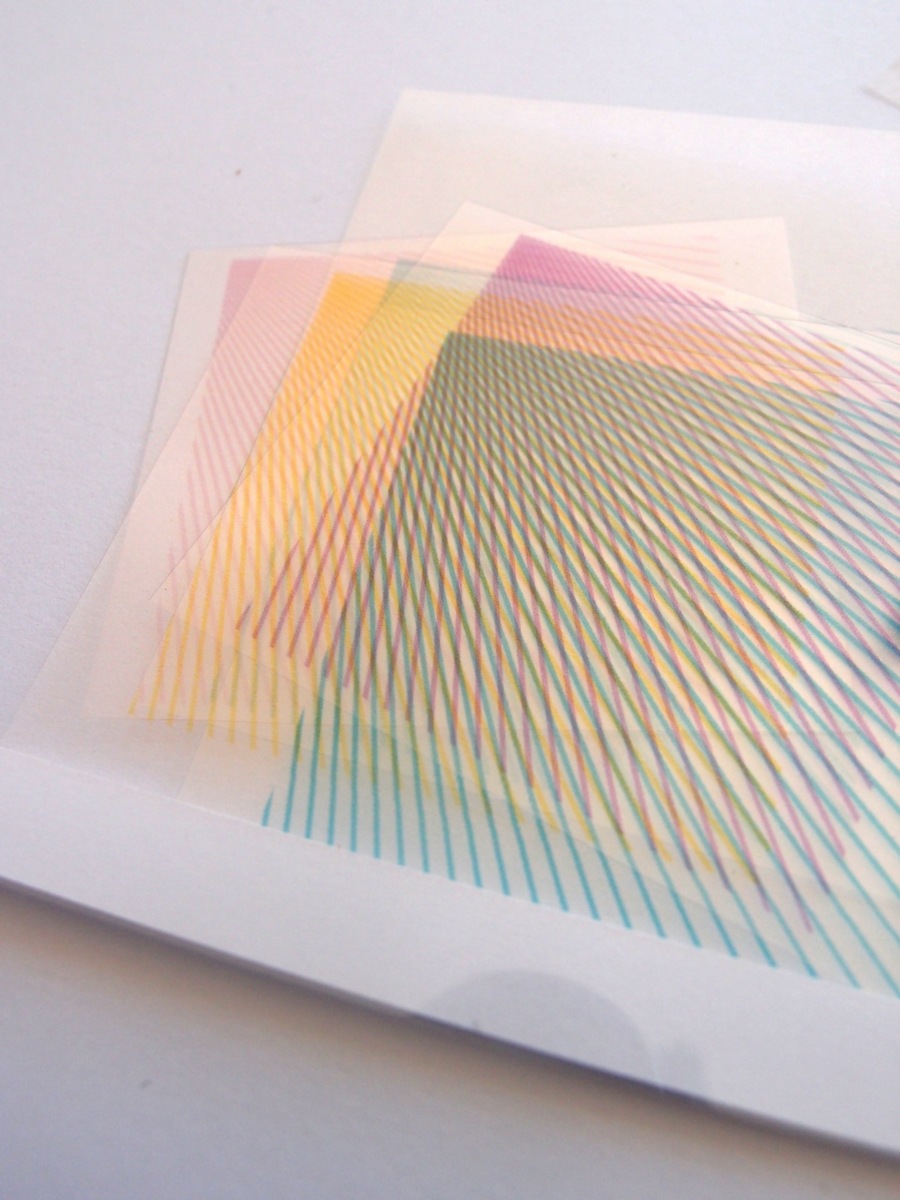

Initially I wanted to research the optical mixing of colour, in the way that happens on a TV screen or in a rasterised print: small coloured lines or dots that combine to create a new colour. I wanted to attain this by layering line patterns on top of each other, both on the computer screen and on transparent sheets of plastic. But when you superimpose two similar patterns you get an interesting wavelike pattern called the moiré effect. I found that effect so interesting that I mad that the core of the project. It's almost hypnotising to see how an existing pattern can invoke a new one by shifting it on top of another layer.

When I look at your process here in your cabinet I can't help but reminisce about Julio Le Parc's work. But I also see other sources of inspiration for this project—what artists have been important for you during the creation of Moiré Jewelry?

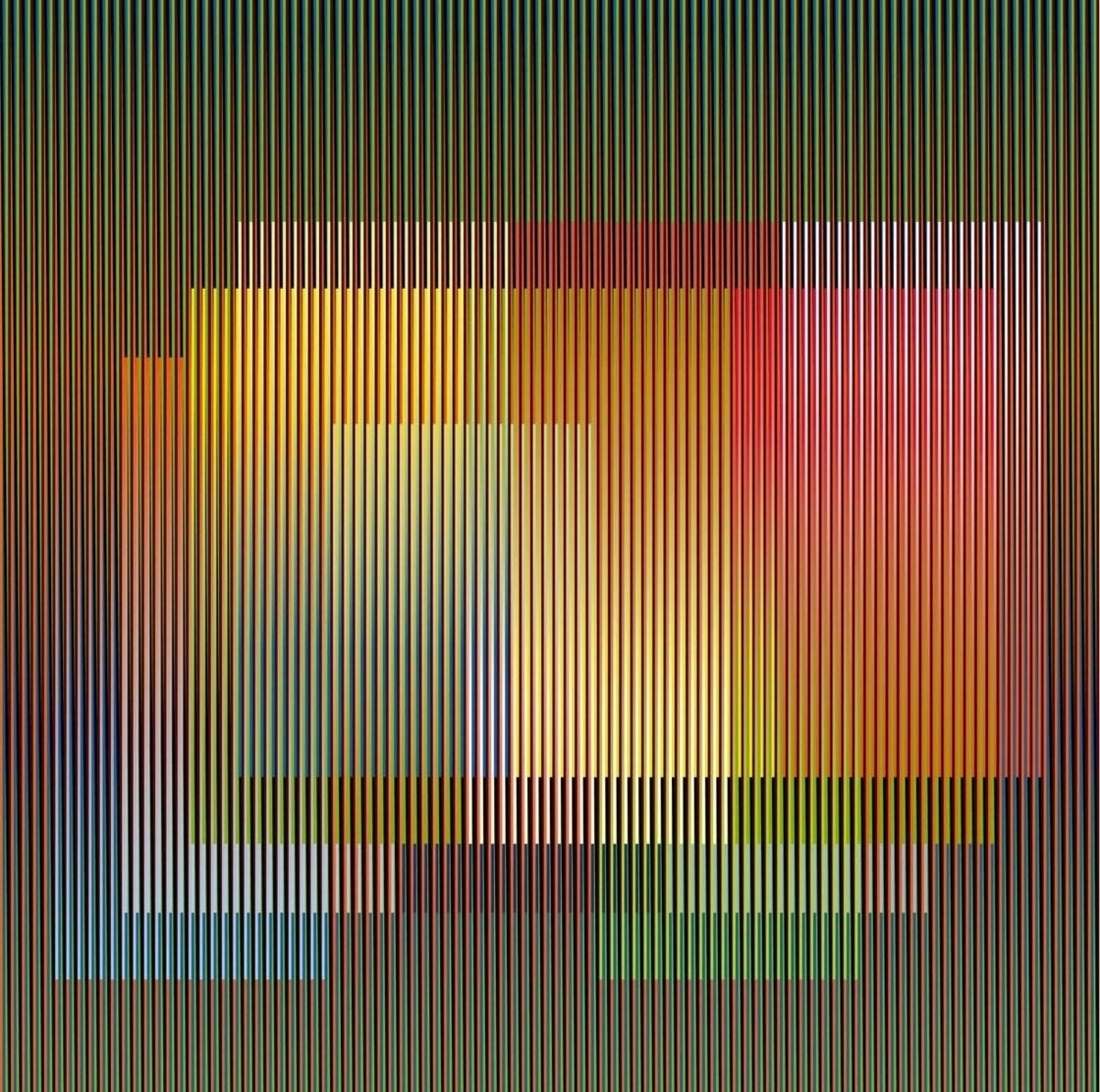

As I just said the optical mixing of colours was my starting point. For that I found a lot of inspiration in the work of Carlos Cruz Diez.

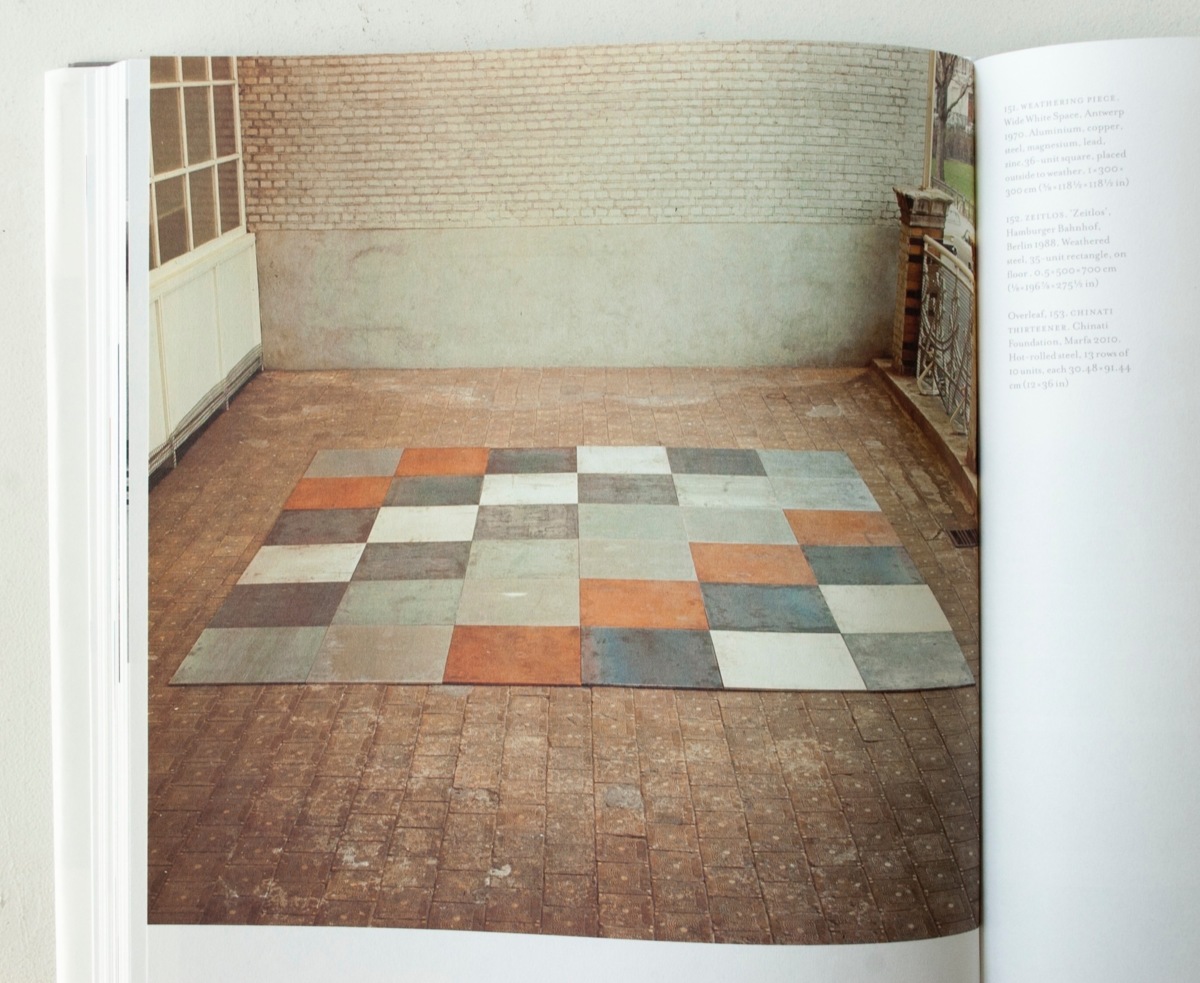

Another maker that's been important to me was Carl Andre. His work is quite minimalist, but it's very much about materials, how they reflect light, how they oxidate, and so forth. His best know works are the 'floors' he makes from different materials.

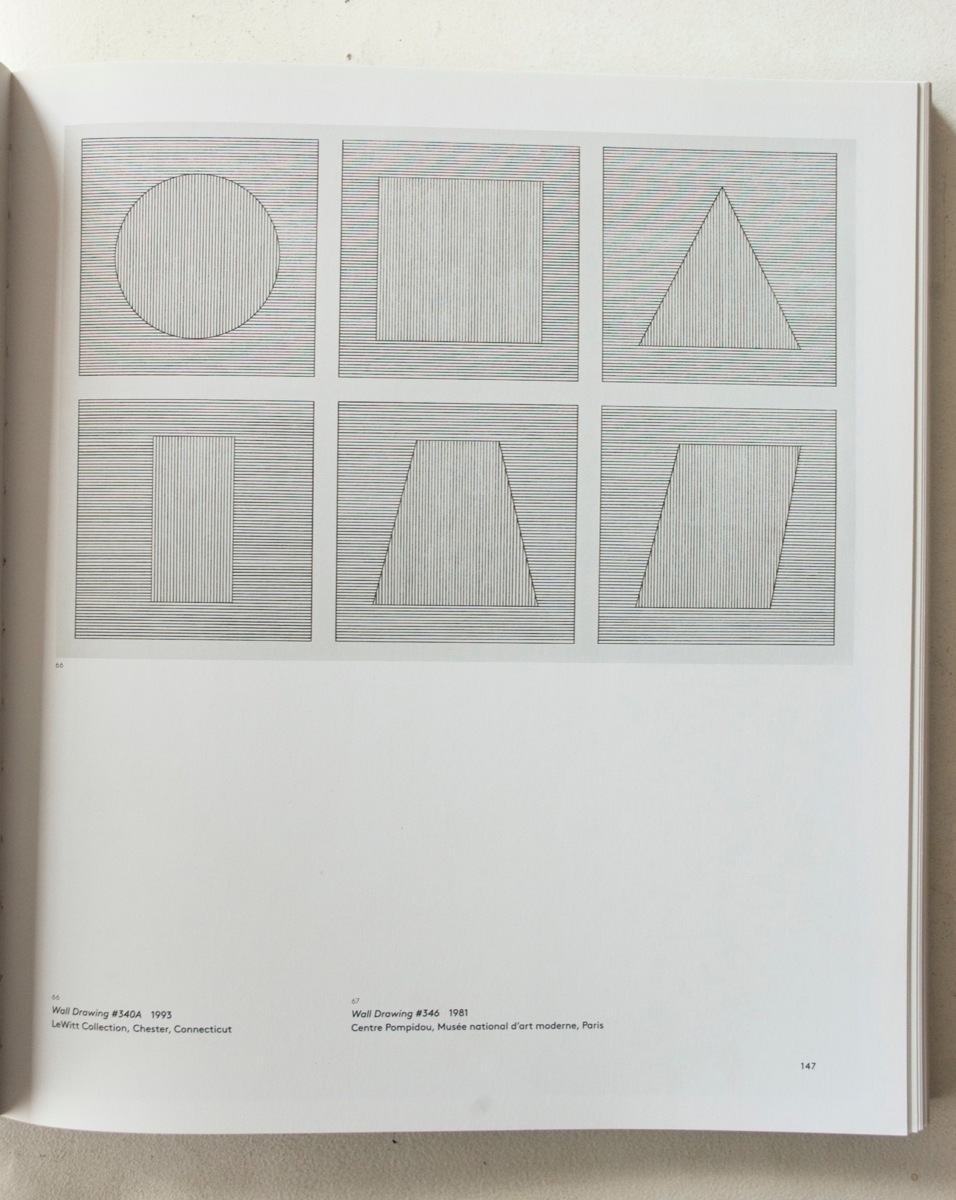

I also show a work by Sol Lewitt in my cabinet, who makes highly abstract and geometrical work. Other than that it's a beautiful work, I find it interesting that he actually doesn't make the works himself—he just writes a recipe for others to execute. This isn't an aspect that I use in my work, but visually—the minimal geometry and abstraction—there's a very clear link.

Carlos Cruz Diez

Carl Andre

Sol Lewitt – Wall Drawing #340A, 1993

You gave some clear references from the art world, but are there any other starting points at the base of your work?

If I look at all my previous projects I think I can discern two starting points: On one hand I delve into the properties of a material, and on the other hand my fascination for certain scientific phenomena, like gravity or clouds. I always try to convey a certain personal fascination in my projects. This doesn't need to be very obvious—ultimately something also has to be appealing—but there definitely always is a conceptual layer.

I won't begin creating a form before I've found an interesting angle or a certain beauty in the material or the natural phenomenon I'm researching. It's not uncommon for me not to know what exactly I'm going to design beforehand. For me the form is only a vessel for the idea, so it usually results out of the material. The aesthetic aspect usually doesn't present itself until the end of a project. I try to add as little as possible, only what is strictly essential: The idea should stand on itself. The core of a project is always my fascination for a material or a process in nature.

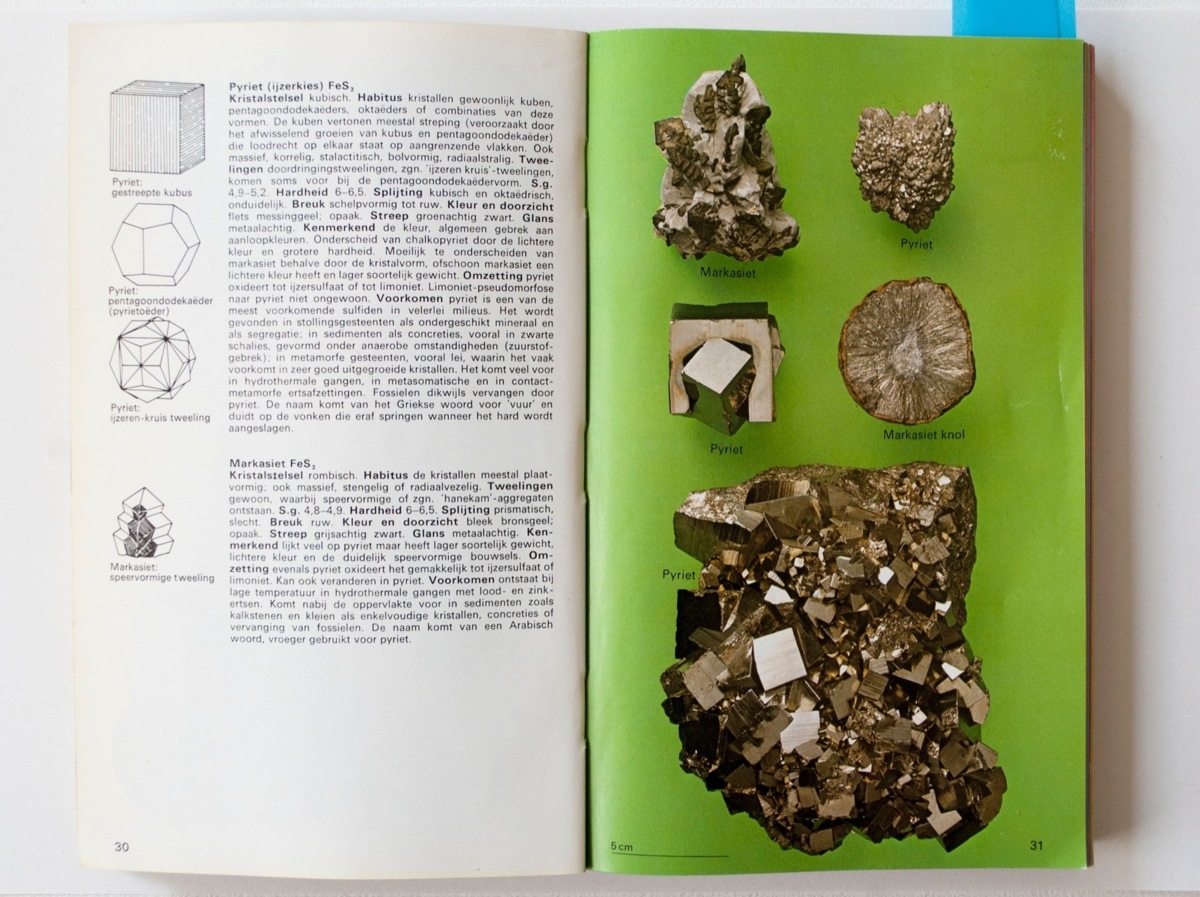

From 'Elsevier Stenengids’, 1974, Peter J. Green

Having the material as a starting point suggests a very physical, hands-on approach. On the other hand you also show a more poetical side with your fascination for natural phenomena. How do these two aspects present themselves in your oeuvre?

I really see materials as characters. When you hold it you get a feeling of how it bends, what is feels like, it's smell… I started out with copper but since then I've also worked with glass, cork, wood, and ceramics. Every time it's a new journey of discover the properties and peculiarities of a material. I want to discover how it behaves, what it can and cannot do, and find the beauty in those limitations. For instance with my Copper Lights and Copper Cabinet it was quite the challenge to guide the material and to stretch it to its limit. In a way I saw that project as a masterpiece in the old sense of the word, a test of my skill in order to join the guild.

Copper Cabinet

Drawer of the Copper Cabinet

My reference point was copper foil as thin as one tenth of a millimeter. I've shown that I was able to use it to create a cabinet that is stable and more or less functional. In order to get there I had to discover a lot of techniques—folding lines, crossing, soldering joints—and use them consistently throughout the design. These techniques have an intrinsic aesthetic value. It's not just about beauty itself, but about the beauty of a principle. The construction dictates the aesthetic. I undress the material, I search for its limits, discover a principle that sparks my interest and then I amplify that. I want to convey a sense of wonder: The wonder about the beauty of a material is my motive.

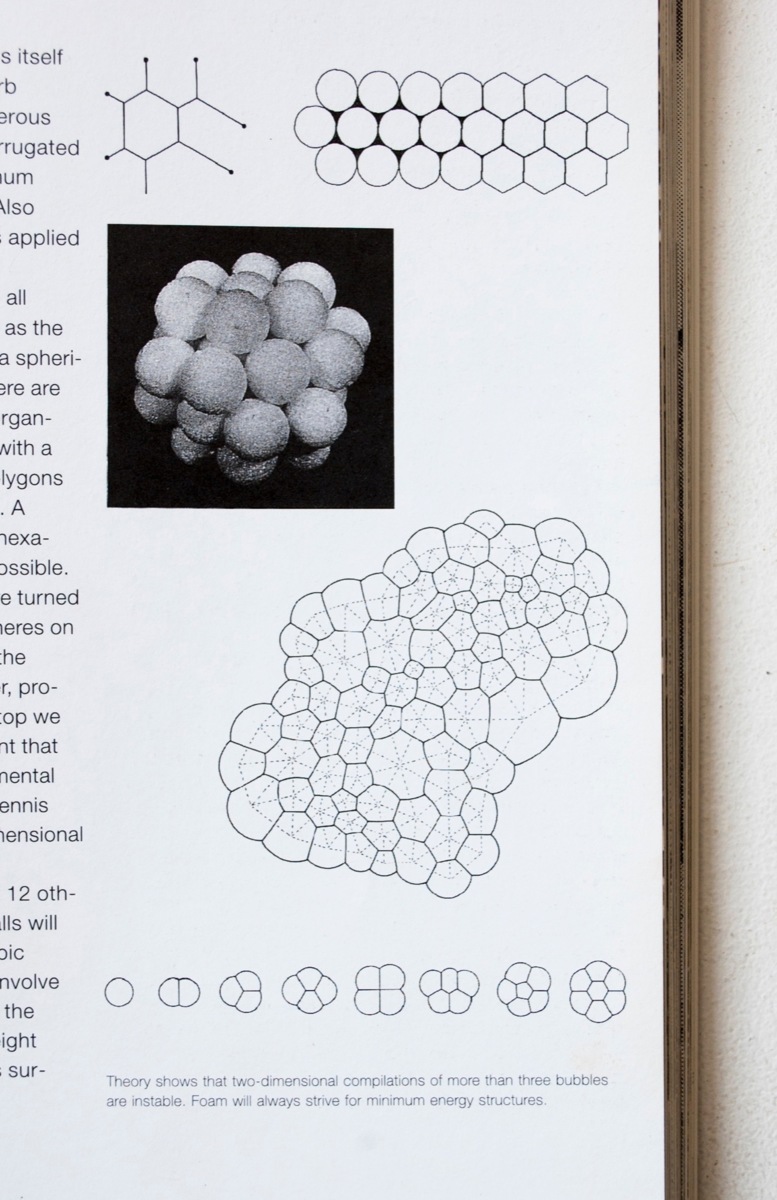

On the other hand my projects often stem from a fascination for nature, and principles of physics in particular. I can be completely amazed by the colours of the sky and wonder why it's that particular colour or why a rainbow is so perfectly round. The Dutch word "natuurkunde" (physics, lit. knowledge of nature) describes exactly what I find so fascinating about it—nature and it's underlying principles. The shapes of crystals for instance is something I find very fascinating. They're appealing to all of us but why do they have these beautiful shapes? Or the fact that honeybees make their hexagonal structures. The hexagon is a very efficient form, but how do they know that? The fact that geometry comes back in nature, or even originates there, is magical to me. Take my Oscillation Plates for instance: A pendulum makes beautiful drawings with the use of gravity. A mathematical pattern appears, totally aesthetic. But the pendulum does what he wants, nature runs its course; I simply show the aesthetic by giving it a form and choosing a material.

Your Moiré Jewelry also came into existence through your fascination for a natural phenomenon. Yet materiality plays an important role in this project.

In order to show the moiré effect as well as I could it was necessary to investigate different materials. At a certain moment I also decided that it had to be jewelry: When making jewelry the choice of material is of utmost importance.

Initially we printed line patterns on sheets of transparent plastic and then placed the sheets on top of each other. This already created a nice effect. You can do great things with plastics, but I was looking for a material with a richer feel to it.

Photo by Fanny Muller

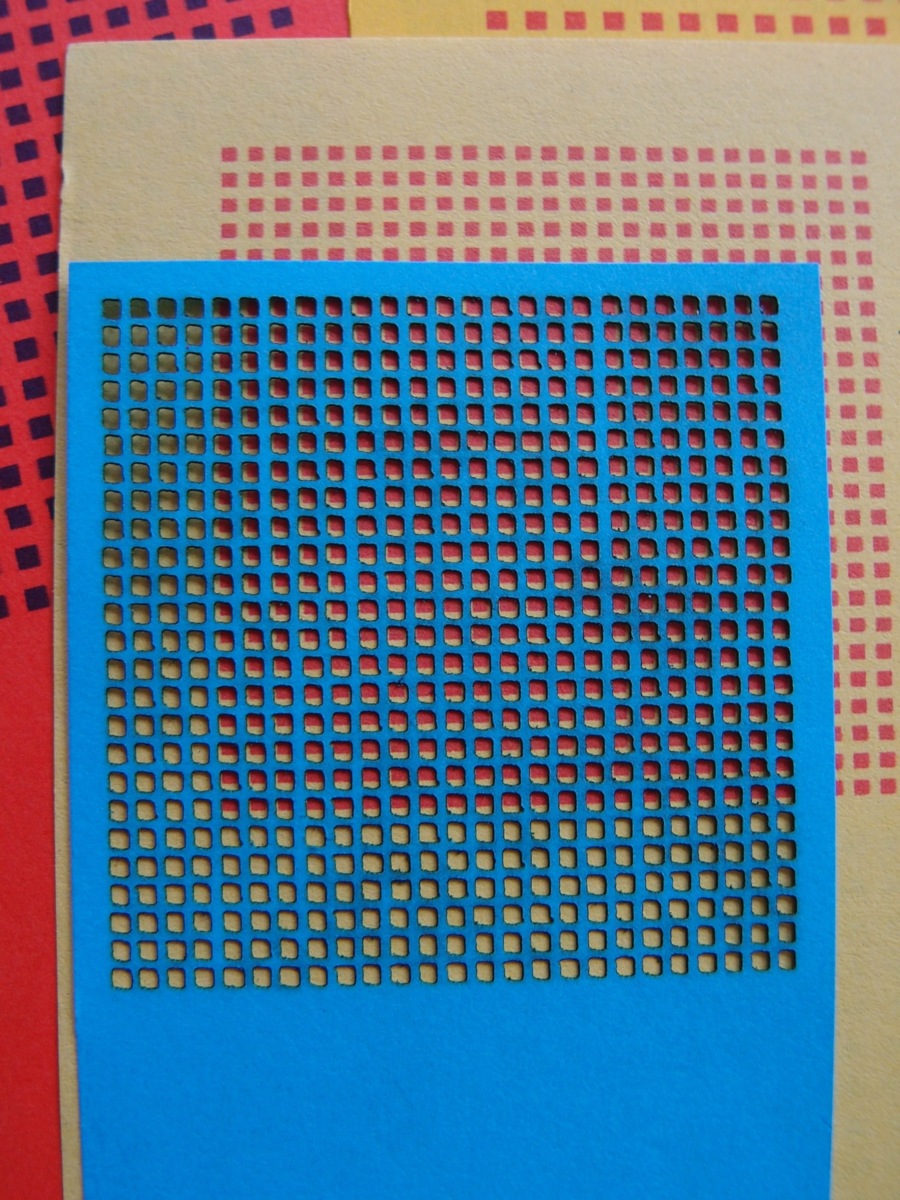

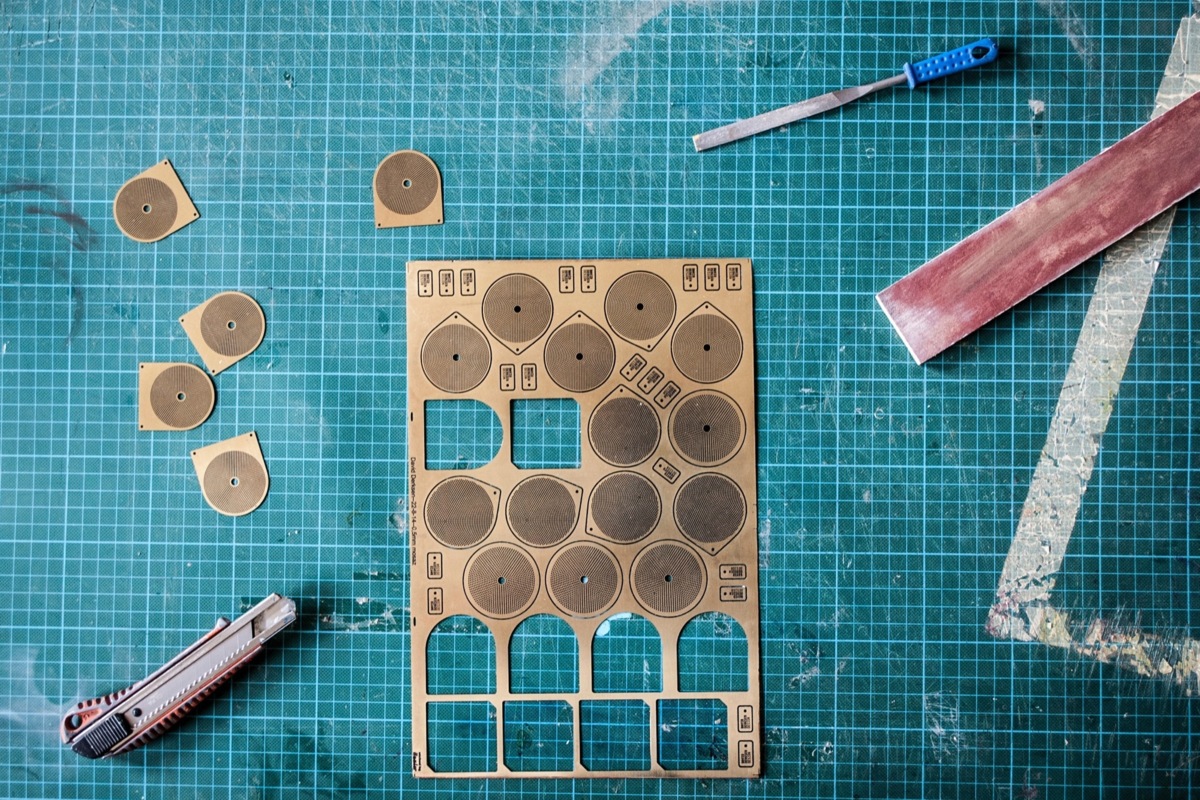

While making Copper Lights I learned to use an etching technique. It's a laborious technique, but it's great for creating beautifully intricate details. Because of the detailed nature of the technique it proved to be ideal for working on small objects such as jewelry. Yet it turned out to be very difficult to apply this technique because the thin lines I etched made the material very weak and fragile, and thus quite unwearable. That's why I switched from line drawings in my design to etched perforations in the shape of circles and squares.

Test papers with layered perforations. Photo by Fanny Muller.

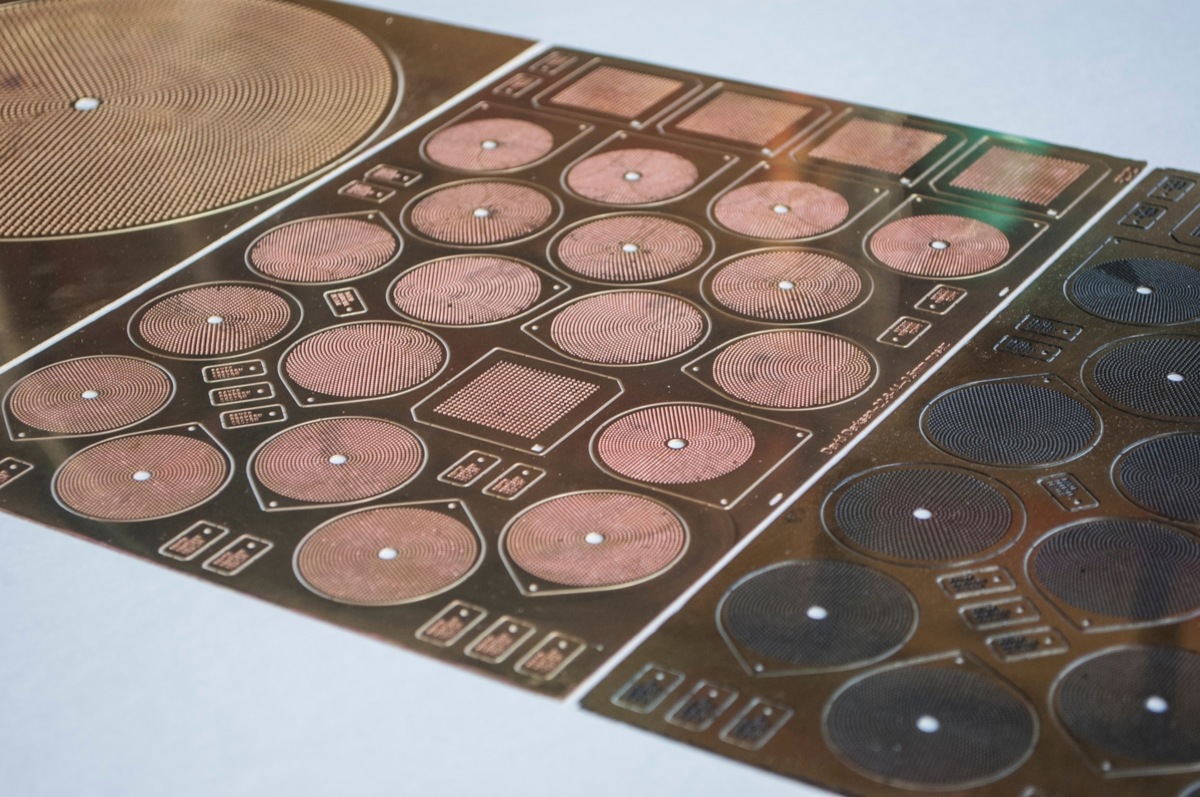

The pattern in the brass is created by etching. Etching is a technique which uses strong acid to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal.

The brass back panels with etched patterns.

The test sheets I made were very attractive to play with so I decided to design something that would both show the moiré effect and be nice to hold and wear. This resulted in a series of four pendants and a brooch. They're all compiled of two layers: a brass back panel with an engraved pattern and a black coated stainless steel front layer with perforations. Brass is a beautiful material with a rich character and offers solidity and weight to stabilise the object. In order to create a contrast I had to apply a black coating to the perforated layer, but powder coating is unsuitable: It is too thick and all the perforations will get clogged. That's why I chose to use a physical vapor deposition (PVD) coating. By process of heating a metal evaporates and the vapor settles onto your base material in a thin layer and hardens. In this case the base material was stainless steel. Brass is not suited for a PVD coating and stainless steel is still quite strong as a thin sheet, which is great because I want people to be able to move and turn the object.

New patterns are generated by moving the identical patterns on the two layers relative to each other. It is both a decorative accessory and a hypnotising toy. Two of the pendants move on their own which spontaneously creates a moiré effect when the wearer moves.

Moiré Jewelry – Style 2

In your Moiré Jewelry both those aspects—material and nature—are present. Wherein lies the origin of this divide?

As a kid I was always playing with nature in my mother's or grandpa's garden. My sense of material probably came from helping my father with work around the house since I was young: I was working with wood saws since I was five years old. I've always been busy making stuff. My grandpa also taught me a lot about art and culture, he often took me with him to museums.

The divide between two subjects was also present in my choice for two types of education: On one hand the Technical University Delft, on the other hand the Design Academy Eindhoven.

After high school I initially had no clue about what I wanted to study. I had a very broad scope of interests—I wanted to go do graphic design, physics, become a pilot… I was looking for something to pour all my interests into in a way that suited me. I wanted something that combined my interests for materials, aesthetics, and crafts, but also my investigative side.

That's when I chose for industrial design at the Technical University Delft. I learned a lot about the technical and analytical aspects of design there: How to calculate how much carrying capacity a material has. How to make a technical drawing or a 3D computer model. There was also a good workshop with great machines, but in the end I spent most of my time behind the computer screen making calculations and writing reports. I wanted nothing more than to start working with my hands, to learn while making. That and it wasn't the most stimulating place creatively speaking, not a lot of inspiration.

I got the opportunity to study at the Design Academy Eindhoven through an exchange program. I gained a lot of knowledge there in the fields of design, arts, aesthetics, and material: It was an infusion of necessary basic knowledge. And it was much needed, because I felt I had a lot of catching up to do. I had to study hard, pay attention, be sharp. But also for the creative part was a very intense period: If there's nothing to show, there's nothing to talk about, that was the credo of the teachers at the Design Academy Eindhoven.

Where at the Technical University you're taught to solve problems, while at the Design Academy you get room to come op with new ones. In stead of having to look for practical applications in society, the Design Academy offers opportunities to explore your individual fascinations. You're allowed to construct something out of personal fascination and for me that has been very valuable.

And after the Design Academy you eventually went back to the Technical University again

I finished the Design Academy in 2009 and was a step closer to what I really wanted to do, but I felt like I wasn't ready yet. I could've started as an independent designer right there, which in a way I did: I made my Copper Lights around that time and took part in the Milan Design Week. But I knew there were a couple of things I wanted to do that would've been a lot harder if I wouldn't be in the structure of academic studies anymore. Exceptional about a university education is that you can really control and formulate your own curriculum. You can write your own thesis project and, if you play your cards right, work with who you want and find the mentors that suit you best. I wanted to work with a big company, like Ahrend: a great company that owns two factories in the Netherlands.

Bruno Ninaber van Eyben

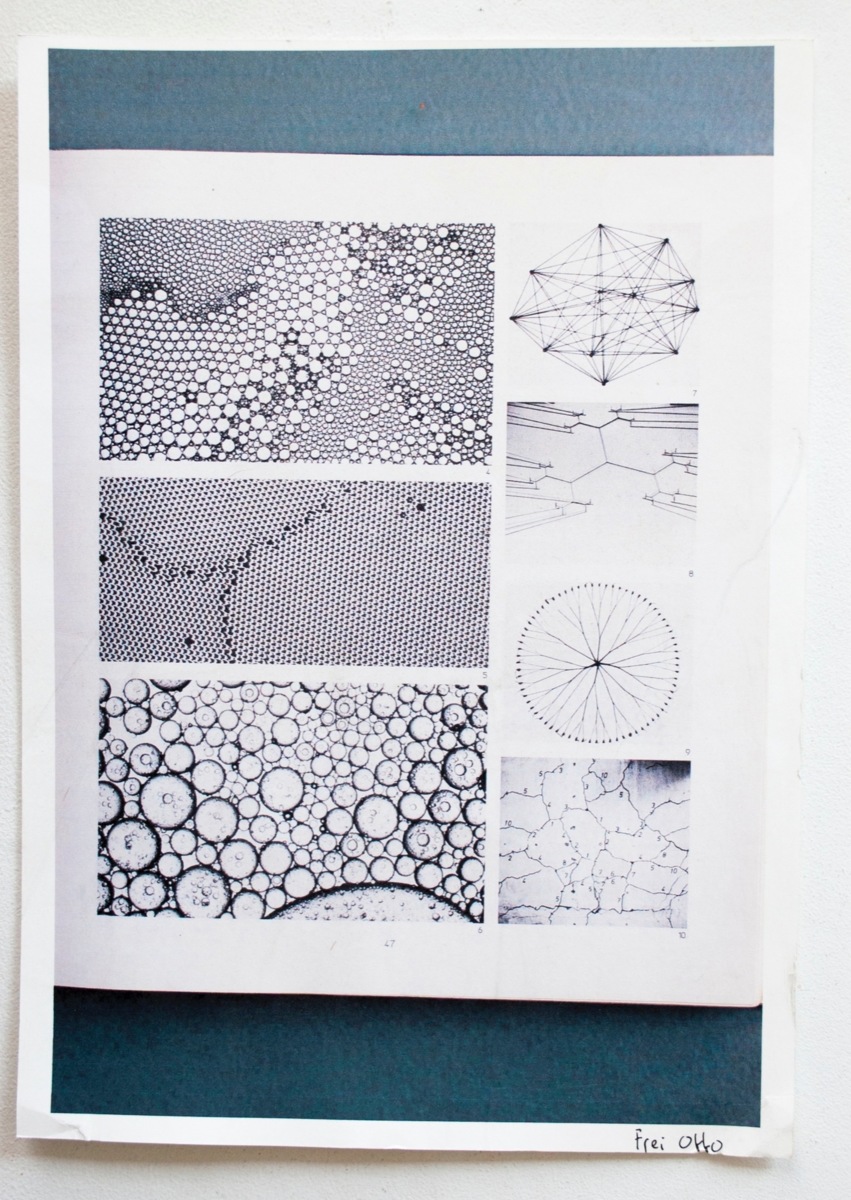

I wanted Bruno Ninaber van Eyben as project mentor. He's a teacher at the Technical University and known for his design of the last Dutch guilder. Because I was going to work with composite materials I called in a professor of aerospace engineering: Adriaan Beukers. Composite materials is a very technical field of expertise, but Adriaan Beukers has a very unconventional approach to it. In his book Lightness he writes about lightweight structures and materials in both nature and history, for instance the bow and arrow or the honeycomb. This was exactly the approach I was looking for: We know the composite material mainly from boats, airplanes, and racing cars, but It hadn't been applied much in furniture design.

It was a very special project for me. I knew the opportunity to work with a big company like this wouldn't present itself in any of the coming years as an independent designer, neither the mentorship of such inspiring people. It was a chance I couldn't allow myself to pass up on.

Bio composite test. A composite material is a combination of two or more different materials that are bonded together. The newly formed material has superior properties to the individual components.

From 'Lightness', Adriaan Beukers

You felt like you weren't ready yet after the Design Academy, and during your Masters you took an important last step. Now you've been working independently as a designer for a couple of years. What do those dynamics generate?

As an independent designer you're required to think as an entrepreneur more and more. It's most profitable to choose one material or technique and become an expert in that field: learn how it works, what you can create with it, and where you can sell it, and at one point you'll be able to capitalise on that knowledge. The constant changing of technique and material, like I'm doing, isn't the best way to go from an entrepreneurial point of view. But in all my fascination and wonder I keep on encountering new materials and techniques I really can't let pass; I feel like I have to find that deepening time and time again, looking for the boundaries of what is possible of all these materials and then seeing how far I can stretch those limits. That's also what keeps it exciting for me. I think this 'flexibility' is what is my strength as a designer.