Unfixed

New Window × Ola Lanko

Unfixed is for sale in our shop.We have invited photographer Ola Lanko to make new work. This work, titled Unfixed, will be presented at Unseen Photo Fair (18-21 September 2014) in Amsterdam and the Dutch Design Week (18-26 October 2014) in Eindhoven. Lanko combines a systematic and analytical way of thinking with a playful visual language in order to investigate the photographic medium. In this interview we will uncover who she is, how she works, and the backdrop of her project Unfixed.

How did you get into contact with photography?

I was born in Ukraine, I've been living in The Netherlands for six years now. In Ukraine I studied sociology. Becoming an artist is not something you aspire to as a Ukrainian youngster. It's not an option; it simply doesn't occur to you. The academies of fine arts are very dogmatic, traditional, and an education in photography doesn't exist. I was interested in what happened in the world around me, so I chose sociology: A broad education, it seemed like a good discipline to gain some comprehensive knowledge. And then I'd see where it would take me.

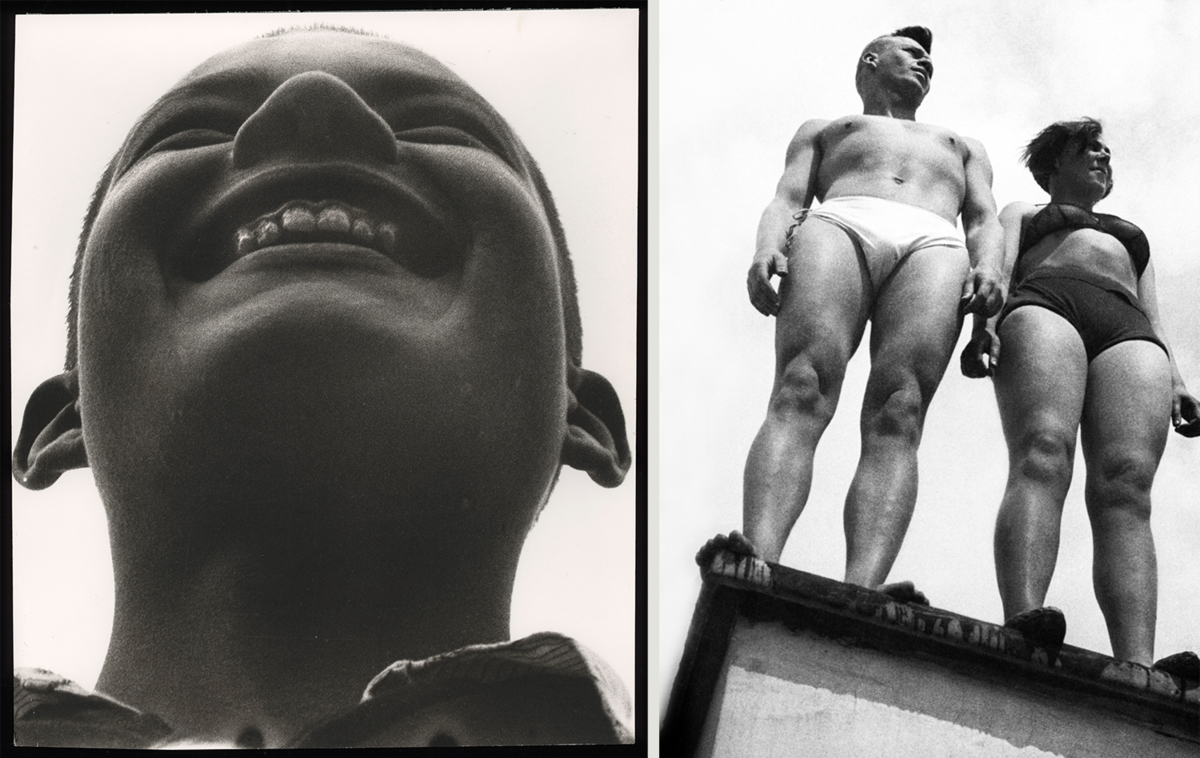

I didn't start taking pictures until later. I found an old camera that belonged to my father in a storage space. Everyone in the U.S.S.R. was an amateur photographer; just like any Soviet family we had a camera and a darkroom. It became a hobby of sorts. This was around 2003; it was a good time in Ukraine, there was a hopeful attitude and the economy was stable. I had friends that were working at a publishing house that was owned by a German investor, and that brought with it some innovative ideas about media and the press from Germany. Through these friends I got a job as a press photographer. When I started I had no experience and was very naive, but because of that I was also quite decisive: I wanted to work and I wanted to learn. I hadn't even thought about art, I was more preoccupied with form and composition in my photography. The constructivists were a big inspiration: Alexander Rodchenko, Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein were my heroes.

The work of Alexander Rodchenko was a big inspiration for Ola Lanko and that same visual language can be seen in her early press photographs.

So photography started as more of an applied job for you. At what point did your interest become more prominent?

An important switch occurred when I went to take pictures at the funeral of a controversial politician. It was a very intense happening; I was taking pictures alongside 20 other photographers, feet firmly nested in between the flowers to get the best shot. The grave was surrounded by crying women, but we never ceased to take pictures. I then realised something I thought was very odd: I didn't feel anything, no emotion. But why? The camera somehow gave me the authority to stand there and take shots of these women. And they let me, because I was a reporter, I had a camera and it was my prerogative to take these photographs. I realised that the medium worked as a divider between me and reality and that photography has an inherent power. I decided to understand this power and I have been investigating it ever since: How an image can affect people, what is its place is in our society and how it's a part of our everyday lives. I think it's fascinating how we constantly surround ourselves with images, but are not always aware of their implications.

After journalism the logical step was commercial photography. This way I had more freedom to decide what subject would be in front of my camera and how I could construct my images. I was craving more control over the images I made. Because the academies in Ukraine did not offer a full education in photography, I decided to go look for one elsewhere in Europe, so I could get better knowledge of the technique. I started to study at the KABK in The Hague, which provided me with a solid foundation, but after two years I realized I wanted to develop more in an autonomous direction and I made the switch to the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam.

In what way do you think your academic background contributes to your artistic practice?

Looking back I see a lot of parallels between the themes I was working with in sociology and what I am now working on in my artistic practice. I was never interested in statistical research, but much more in socially relevant subjects such as symbolical values within culture. The subject of my Master's thesis in sociology was symbols in religion, because religion is the receptacle for the symbolical layer in society.

Bouillon cube. Example from Ola’s book Required Reading which explores the concept of visual literacy.

All the ingredients of a bouillon cube photographed separately, illustrating that things as we know them can sometimes be much more complex than they seem.

In my work I have a critical view on recurring and universal symbols in visual culture. I want to make people aware of the complexity of an image. It's easy to experience an image as attractive, but I'd prefer it if people would make a bit more of an effort to dissect an image. Certain parts and elements refer to aspects that don't necessarily lie within the frame of the images themselves. The state of the viewer also has a lot of influence on how he perceives a photograph. His nationality, if he's hungry, if he was just in a fight with a friend, etcetera. There are so many elements that influence the way we experience images and we're usually only barely aware of that.

Another example from Required Reading which illustrates how a red dot placed on a different background can suddenly turn into a Japanese flag.

An important piece of my graduation work at the Rietveld Academie was a book on visual literacy titled Required Reading. It is a handbook of sorts on how one can dissect an image with the use of linguistic modules. I applied linguistic concepts like syntax, morphology, and pragmatics to images to help the viewer learn how to 'read' them. A photographer wants you to see his picture in a certain way and he has the camera as his tool to engineer that. As a viewer you should never forget that. You should never take an image for granted; I'm convinced of that fact and in my work I try to emphasise it.

Ola’s most recent project Romantic act of reason shows the way she processes her ideas. What seems chaos at first is actually a carefully arranged and organized collection of thoughts where anybody can find new insights and ideas.

The critical view towards the images that surround us is an important aspect for you and it recurs in many of your projects. Are there any other important themes or viewpoints in your work?

The subjects I treat in my work originate in my personal interest or wonder about current events or phenomena that occur around me. I see something and start dissecting it. Once I've chosen a subject the first thing I want is to understand it in all its facets. The research I do and the different story-lines I develop usually become part of the final outcome—in a way this means the outcome becomes a visualisation of the process and a representation of the complexity of the subject.

But in the end the subject is not so important, and neither is the final outcome itself. What I find more interesting is being able to get the thought-process within the viewer going. I don't impose an opinion, the work should be the starting point of a change in the viewer's mind. The acquisition of something when you look at the work, something you take with you and that influences the way you think—that is what makes the work. In such a way the experience and imprint of my work can echo on for minutes, hours, days, months or years. In a way it only becomes an artwork once the viewer interacts with it—the viewer becomes a co-creator of sorts.

For her project All year round Ola photographed one location for each day of one year, resulting in a panorama that is about twenty-one kilometers long. The project has a very strict structure and becomes an abstract visualization of the notion of time. This video is a documentation of her installation. You can explore this project on www.1year365days.com.

This way of decoding and dissecting images with the use of scientific tools sounds like a very analytical and methodical way of working, but your work also has a very poetical side to it. You call yourself a rational romanticist. How do you unify these two seemingly opposing aspects in your work?

Required Reading is still a very important work for me. In a way it became a guidebook for my later projects, it functioned as a sort of skeleton framework. In spite of incorporating humor, I operated very systematically and the end result became rather dry. In an attempt to counter that I went in search of a way to fulfill the romantic side of photography; I wanted to understand why I fell in love with the medium and where this love comes from.

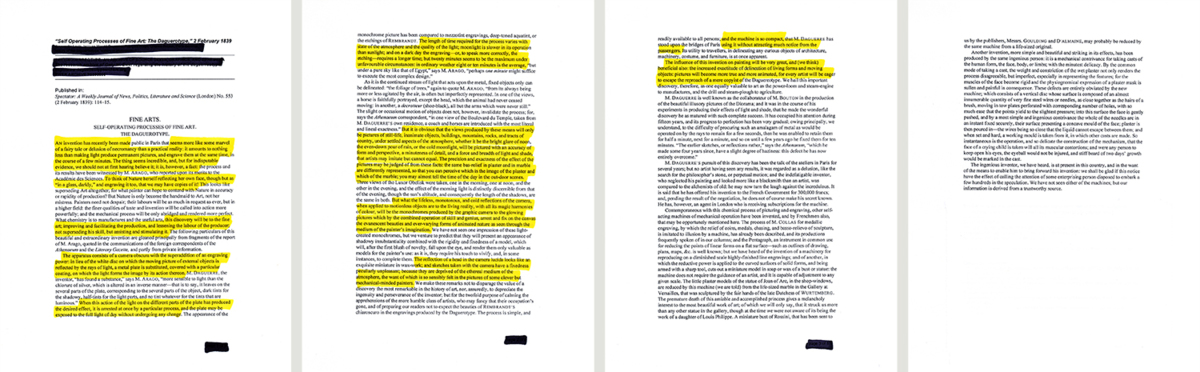

A reproduction of one of the first comments in the media on the invention of photography. It was written in 1839 and published in Spectator, a weekly news journal. These first reactions became a starting point for Ola’s project Photofetishism which explores photographic qualities in a poetic and intuitive way.

While reading one of the first articles on photography by Louis Daguerre, published only shortly after its invention, I came across a passage that made a big impression: ~"Photography is a process which gives Nature the ability to reproduce itself."~ So it is not about the creator; the creator plays no other part than facilitating the camera. This connected seamlessly to my personal struggles with the ego in art. Why is my view on the world more interesting than someone else's? I used to think I could place myself completely outside of the frame—the image—but now I know that will never be possible. There will always be a maker, with his own idea and his own vision. And that is also an added value, it is something others can react and reflect on. But like I said before I am not in the center of my work; it is the viewer who completes the work.

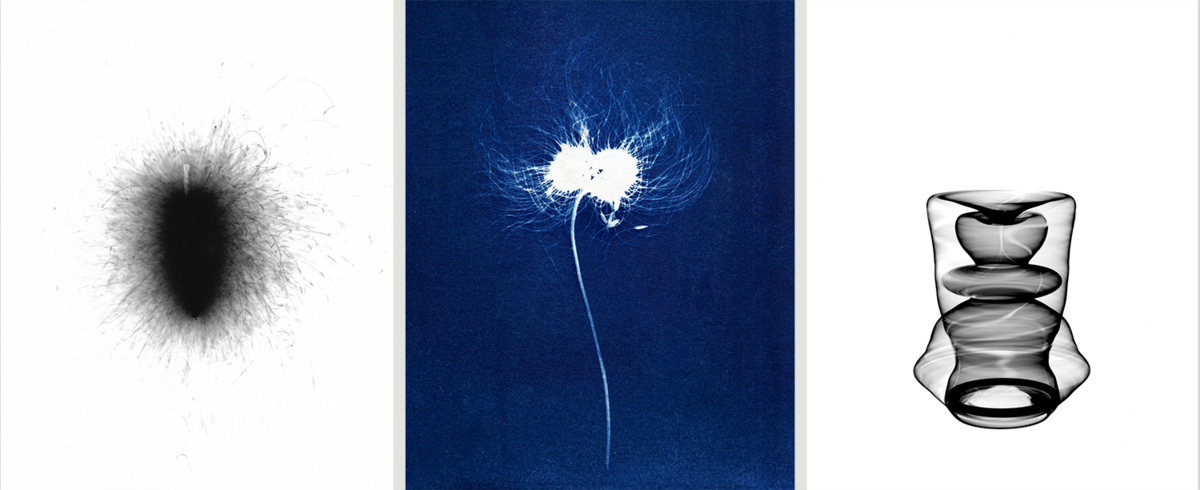

Sparklers, Phototrophes and Vases: three chapters of the Photofetishism project with which Ola explores the notions of time, nature and light.

That quote by Louis Daguerre became the starting point for a quest for understanding love, nature, chance, accuracy and systems in photography as a physical medium. As you’ve already mentioned I see myself as a rational romanticist. A rational approach and reason as a driving force in my practice go together with a strong emotion as a source of aesthetic experience. I establish the rules, relying on my rational choice, but don’t underestimate the power of subliminal beauty that can be brought to the foreground by means of photography.

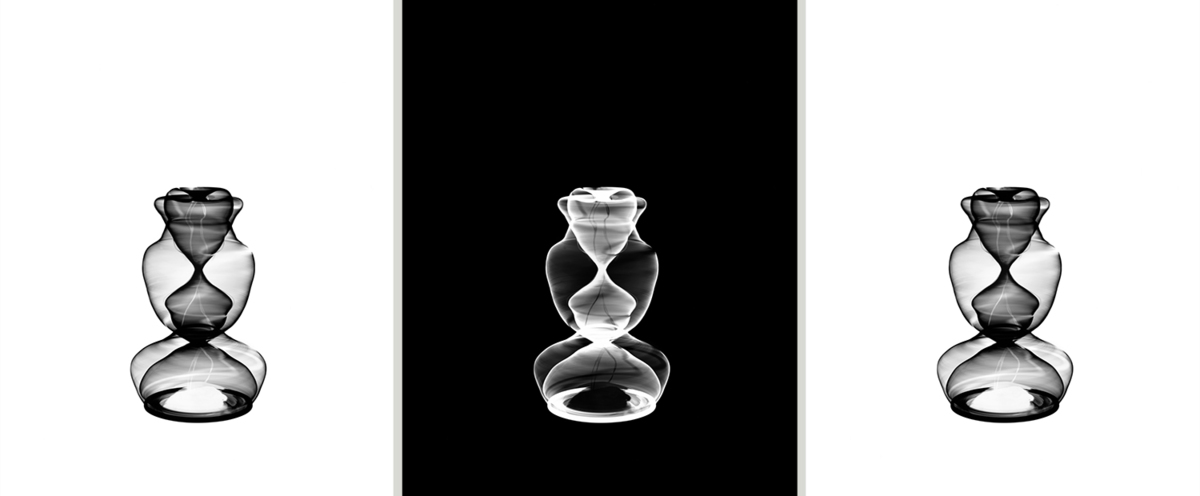

Photofetishism consists of a few smaller series of works and focuses on the nature of photography and its special features that allow us to capture unique and transient moments. In this project I explore time, light and photographic materials. I take photographs directly on photo paper or photosensitive material, creating unique imprints of unstable matters that only leave their traces on the surface of the paper. Photofetishism is about obsession, craft and material. The smaller series of works elaborate on special features of the medium. For example for Sparkles I literally depicted the life of a burning sparkler. The shutter of the camera was open while it was burning, and in this way the whole process is captured and its memory is preserved in a photograph. For the series of Phototrophes I decided to let nature reproduce itself in the most direct way I could find. I used an old photographic process called cyanotype and made series of photograms with plants. I simply put a flower on light sensitive material and let nature do its work creating a copy of itself on two-dimensional surface of an image. For the series of Vases I was investigating the notion of time and illusion that photography can create. I constructed a structure made out of a light-emitting shoelaces that, while turning, appears on the photograph as a vase. So what you see as volume is actually made by light and has no material structure underneath. I made a series of 25 unique photographs that all exist in a particular depicted form only in the picture. It is a process that can never be exactly repeated, because if you’ll change a shape of a light-emitting shoelace or a shutter time of the camera, the vase will look different.

This video shows a light-emitting shoelace turning on a turntable. It was used in the process of creating the Vases series. At this same moment the shutter of the camera is opened, capturing the turning object as a two dimensional image.

The Unfixed project is in a way a translation of Vases. Can you tell a bit more about the methodology you employed to make that translation?

Unfixed is a small commentary on the unstable nature of photography—another quality which the medium possesses. Even though photography is fully integrated into our daily practice and no one can escape its presence, not everybody is aware of the actual instability of photographic materials. When printed on average photo printers, photographs seem like they will last for a long time. But the truth is that it only takes a bit before colors start to fade or change. Aging and disappearing is something that is very typical for the photographic medium. From the beginning the issue of fixating the image on a light-sensitive surface was the main challenge for photography pioneers. Considering the modern situation, the insane amount of imagery being produced, the instability of the photographic medium doesn’t seem that terrible. It seems like the medium itself takes care about its ability to multiply wildly.

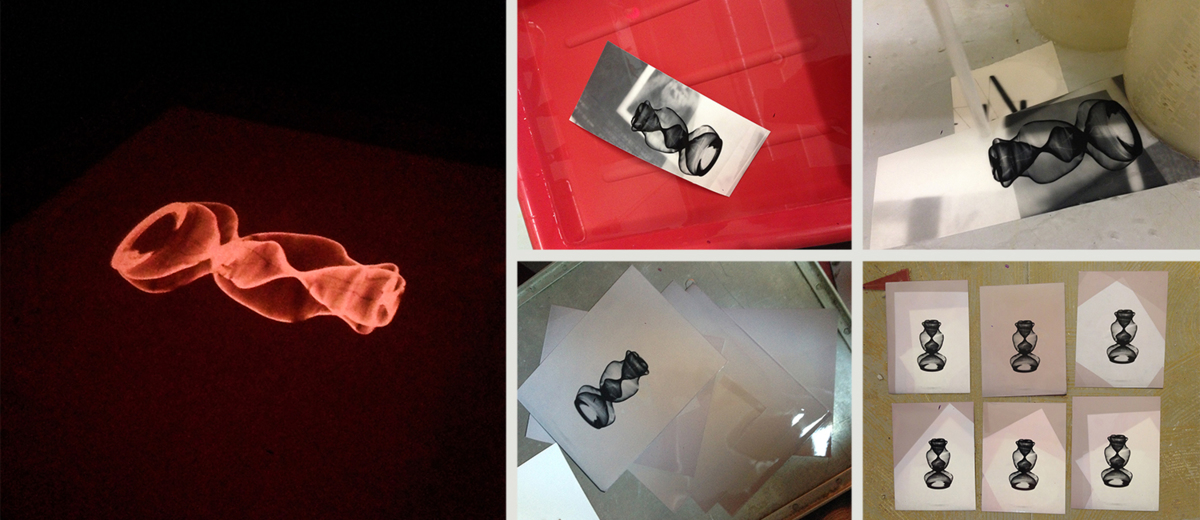

Ola's studio setting while working on her Photofetishism project. She used a 10 x 8 inch view camera and took her photographs directly on light sensitive paper.

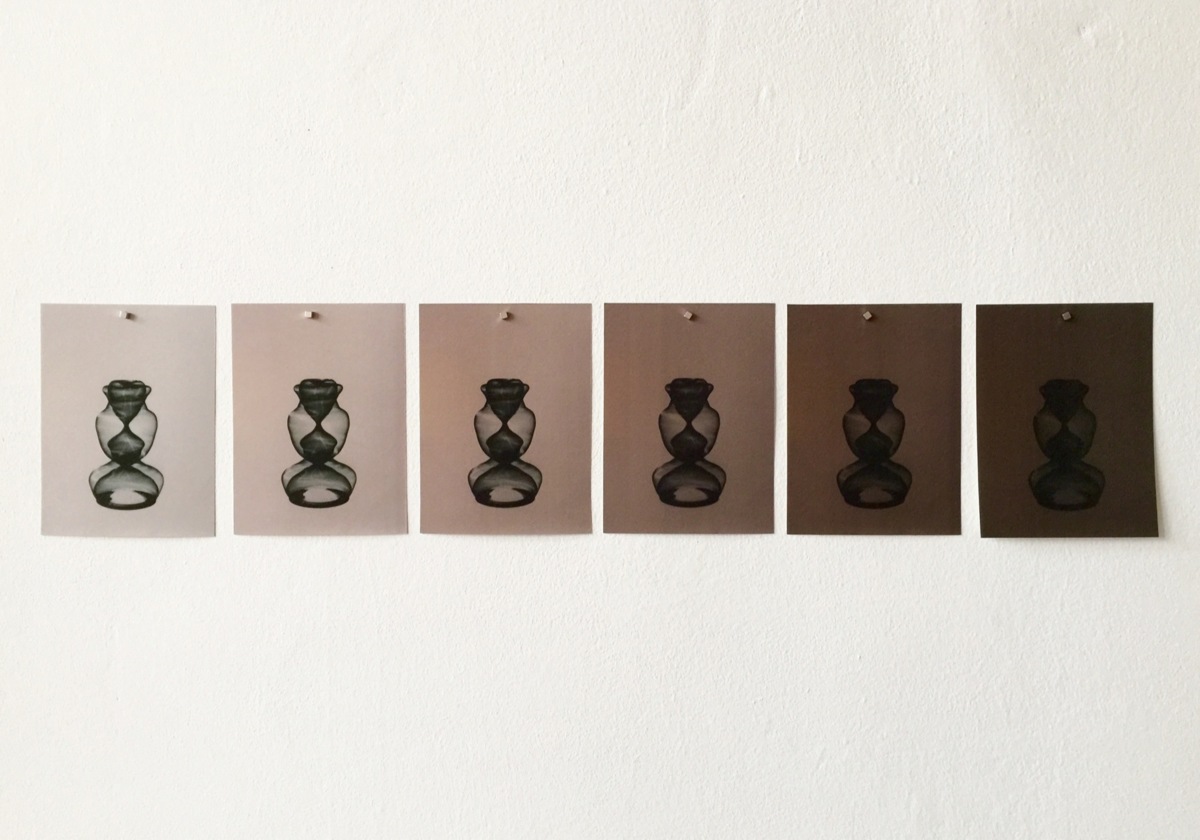

Ola printed her Unfixed series in a darkroom in an edition of 100 unique silver gelatin prints. Following the usual photographic process, one would fixate the image to prevent it from fading. Ola skipped this step to emphasize the temporality of the medium.

It is hard to predict when the image will become completely faded – it depends on the light conditions and the image itself. In the first 10 minutes the image will look like one above, which was exposed to light without red filter, and it can take years to lose it completely.

So when New Window asked me to make a new work I decided to look at my series of Vases from another perspective and use these images to explore the transient nature of photography. In the darkroom I printed 100 unique silver gelatin prints. According to the process you have to expose paper to the light, develop it in certain chemicals and fix it using other chemicals. I decided to skip the last step and leave the photos unfixed. Photo paper is almost non-sensitive to red light, so in order to keep the unfixed image, I placed the picture behind red glass, which slows down the process of disappearing. Eventually the image behind the glass will fade, but it will happen very gently. By this little gesture I want to make people aware of the inconstancy of photographic materials. The subject on the photograph, a light vase, is also temporary and unstable in the same way as the unfixed framed photos behind the red glass are.

In the darkroom, Ola found a way to make a copy of a unique print without using any additional elements. Every print has been in contact with the original image. Therefore Ola had to make two copies: first an inverted one and after that one that looks the same as original.

For me it was a challenge to find a way to keep the uniqueness of one image yet at the same time to make an edition of 100, but I found a solution to solve it. To multiply the original but still keep it as related as possible I had to first put it on top of light-sensitive paper and expose it. As a result I’ve got an inverted image of the original. Afterwards I would place the received image on top of another sheet of paper and then I’d get a copy which resembles the original image. I must admit that this way isn’t the easiest way to reproduce an image, but for me it was important that every photograph from Unfixed series had a direct contact with the original vase. Through the multiplicity of the series, the original loses its value and eventually disappears in the same way photographs will fade and diminish. I think that we shouldn't be afraid of losing an image; on the contrary, we should value its impermanence. The acceptance of this photographic feature can be liberating and bring more enjoyment into everybody’s personal relation to photography.